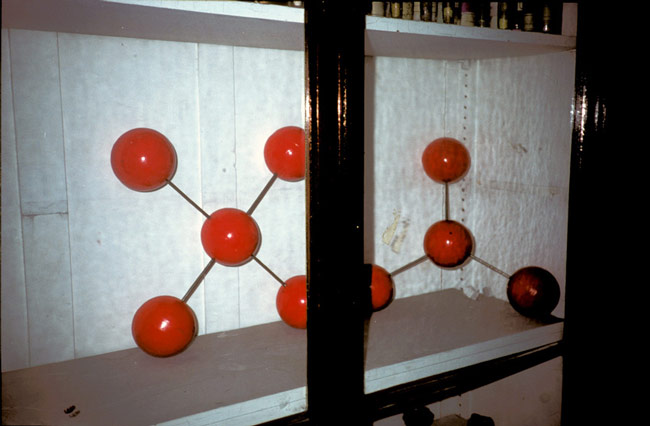

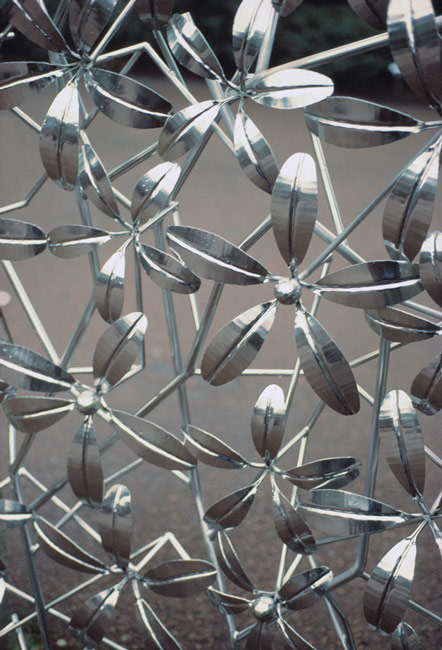

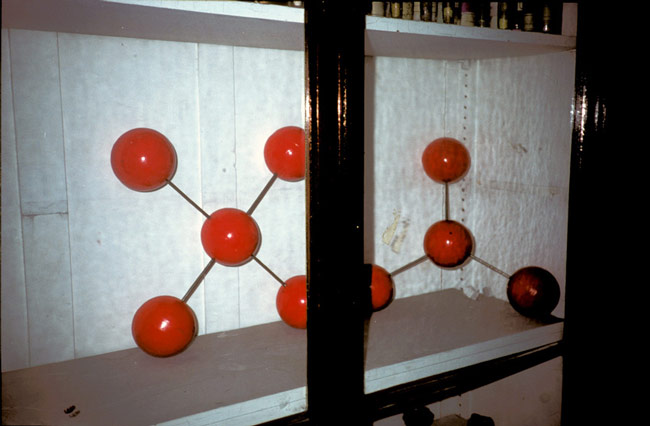

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004 installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 20040304 | 2004 | INFO

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 20040304 | 2004 | INFOSimplicity of Seeing

The Rhetoric of Beauty in the Photography of Martin Fengel

Susanne Gaensheimer

“If images don’t do anything in this culture,” began American art critic Dave Hickey’s spontaneous remarks on the idea of beauty in contemporary art (contributed on the spur of the moment in an early-1990s symposium on the state of art and art criticism), “if they haven’t done anything, then why are we sitting here in the twilight of the twentieth century talking about them? And if they only do things after we have talked about them, then they aren’t doing them, we are. Therefore, the efficacy of images must be the cause of criticism, and not its consequence – the subject of criticism and not its object. And this,” he concluded, “is why I direct your attention to the language of visual affect – to the rhetoric of how things look – to the iconography of desire – in a word, to beauty!”

Hickey’s plea for beauty, initially interjected rather provocatively and spontaneously at a conference, led in the end to a small volume of four essays on the political power of beauty in art that had some significance in artistic discourse of the 1990s. Using the example of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, whose censorship had attracted great public attention at the time, Hickey decodes beauty as one of art’s primary visual strategies that artists right back to the Renaissance have deliberately and successfully deployed to give the political and ideological content of their paintings the seductive form required for the power and ambition of the particular patrons to flow subtly and subversively into the system’s inherent network of signs and codes. Hickey’s revision of the concept of beauty in the early 1990s came at a time when in contemporary art even the slightest hint of the aesthetic still drew the stigma of the affirmative and commercialism. Now, only ten years later, Western art and culture production is characterized by an advanced disintegration of cultural categories. Reacting to the extreme social and technological developments of the late twentieth century, in the course of the 1990s art deliberately crossed the boundaries to design and commercial production, and fundamentally transformed our assessment of aesthetic values. A crossover encompassing all fields of visual and cultural production, coupled with the fundamental loss of the notion of the authentic through the virtualization of our visual experience, has dissolved the taboo between high and low and ultimately re-evaluated the alleged profanity of beauty. But all the same, we still feel strangely caught out when our first reaction to a work of art is to think: “How unbelievably beautiful!”Beauty permeates Martin Fengel’s photographs. Without really being able to pin down where it exactly lies, and knowing that in an age where we can no longer call on the classical concepts of the beautiful to talk of beauty is like walking on thin ice, it still seems to me to represent one essential feature of his pictures. Their beauty is unmistakably before me, bar any stylization or exaggeration: simple, almost subdued, and as a matter of course. Unlike other visually seductive works by artists of his generation, Fengel’s aesthetic is not refracted by the metalevel of a theory of perception, by technical manipulation or by references to the artificiality of our modern ways of seeing. Quite the contrary, Fengel photographs what he sees, simply as it appears, be this the urban civilization around him or the world of nature. That beauty is tied to the mere appearance of things – to the “rhetoric of how things look,” as Hickey puts it – is symptomatic of a time when perception is drawn more and more to surface phenomena. Channelled by the identification mechanisms of late capitalist society, increasingly defined through the superficial appearances of things, and by cognitive factors such as the radical acceleration of seeing and the interface structures of the digital media, our relationship to the world has become ever more aligned to the principle of surface in recent decades. Fengel’s photography is “superficial” in the cognitive sense of the word, because it grasps the nature of a thing through its mere appearance. This is most apparent in his photos of inflatables such as air-beds and plastic animals, which he shows in such close detail that the object itself disappears completely behind its surface. The shiny materiality and trendy colourfulness of the bulging blow-ups, their strong tension and the reflections of light on their strange, almost obscene folds break loose from the objects’ actual function and become autonomous formations with an independent, extremely decorative quality.

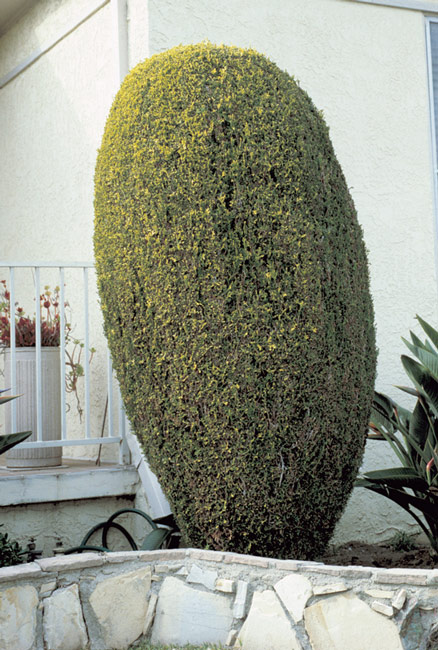

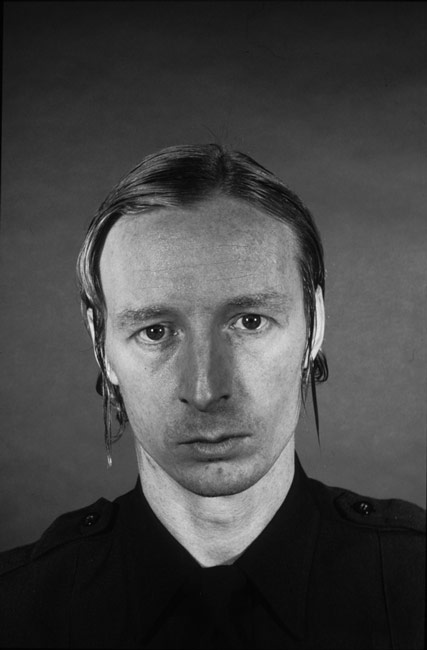

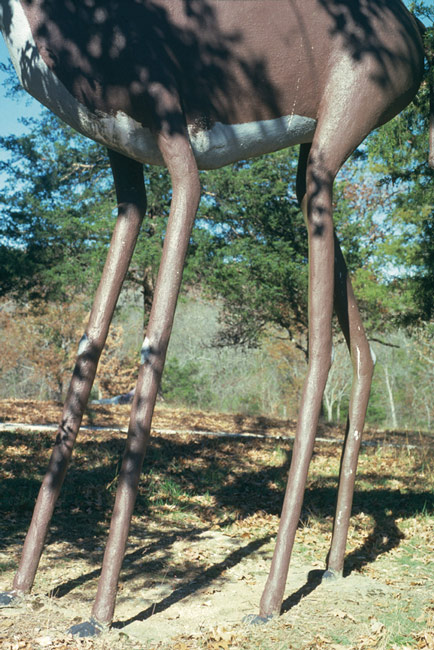

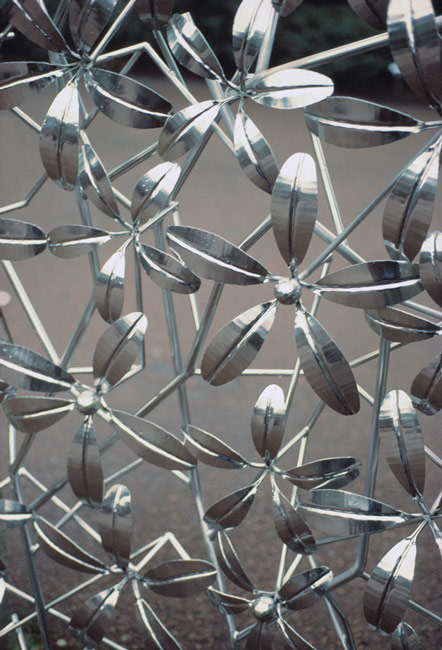

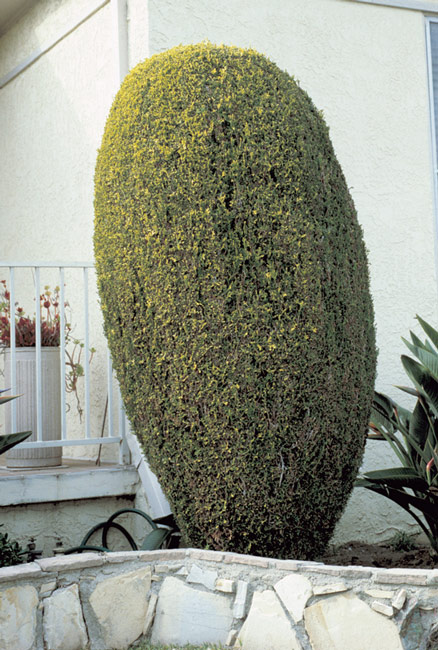

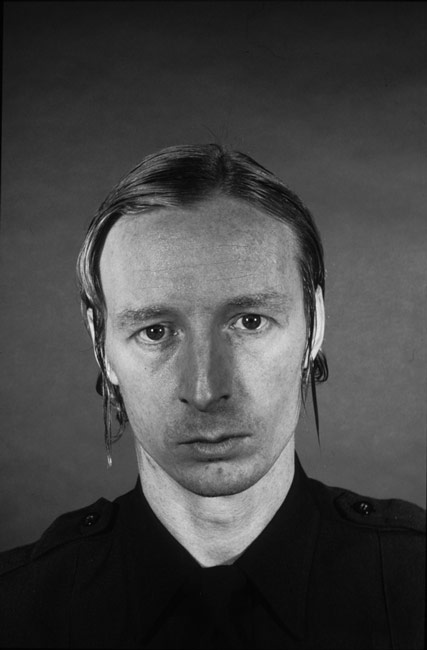

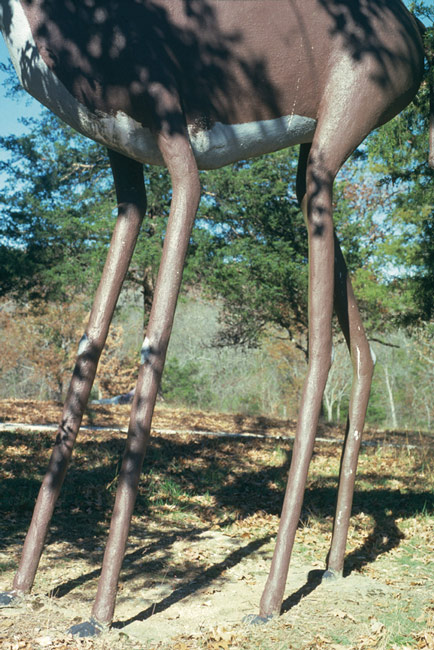

Martin Fengel’s understanding of beauty is deeply democratic. It is found in the normality and averageness of the everyday just as in the incredible perfection of nature. Faces of famous and unknown people fit as equals into a series of ordinary and extraordinary things and situations. What they all share, however, is the great secret concealed behind the obvious. The objects and situations that Fengel photographs in series like 0304, T and M always look like themselves, but at the same time they also look like something completely different. We all know the plastic buckets on the floor and the peculiar piece of furniture, we have often seen the garden hedge, cut painstakingly but slightly squint, and the eccentric amusement park figures where we recognize the stereotypical physiognomy of particular characters; we remember signs, materials and structures. Yet, nonetheless, the motifs in Fengel’s photographs seem so divorced from their actual context that they defy any definition. They are familiar and strange in one, specific and ambivalent at the same time. In a similar way to the photographs of William Eggleston, Fengel’s pictures formulate a poetry of the mundane, seeming both banal and highly charged; they imply – as single pictures and as series – processes and stories that run in our imagination like a film or modern fairy tale. The compositions within the photographs and their arrangement in series seem to be incidental, but both are in fact closely calculated by Fengel, in order to communicate as precisely as possible what he sees in the respective situations as well as in the relationship of these images to one another. Often Fengel takes the camera angle and perspective right down to the photographed objects, putting himself on a level with them out of a deep and sincere appreciation for their mere existence.

Fengel’s staggeringly beautiful photographs of trees, leaves, branches, and flowers in woodland or open landscape, in particular, pose the question of how the artist succeeds in reproducing “nature” without critical distance, and yet without banalizing it. In his Aesthetic Theory Adorno points out the fundamental break in Modernism in representations of nature. The idealist relationship between nature and art that determined the depiction of “natural beauty” from its beginnings in the first perspectival representations of landscape in the painting of the Renaissance, through the symbolically charged landscape painting of the seventeenth century to the last stand of the spiritual dimension in Romanticism, cannot survive man’s alienation from his environment in the modern age. Even in Impressionism, the striking intervention of technology and urbanization flows into the representation of landscape, both cognitively and in the choice of motifs, showing “wounds of nature” that according to Adorno have to be integrated in the modern consciousness. The idea of nature has been increasingly co-opted and objectified through technologization and commercialization in a development whose vanishing point Adorno sees in modern art’s recognition that “nature as a thing of beauty” can no longer be depicted: “For natural beauty as manifestation is its own image. To depict it has something tautological that, in objectifying the manifestation, gets rid of it at the same time.” In an age of the total mediatization and marketing of nature, its representation turns into “an ugly grin”.Martin Fengel’s series “Forest” does not show nature broken. It neither points to its “wounds”, which today are greater and more permanent than ever before, nor does it convey a visual experience based on the virtualization of nature in a mediatized and digitalized world. No, it shows very direct photographs of very simple motifs in the forest: tree trunks and the specific texture of their bark, a group of twigs and leaves, branches, undergrowth and the withered leafage of the forest floor. It is characteristic of Martin Fengel’s photographs that he makes no attempt at all to manipulate or idealize his motifs. Quite on the contrary, he uses an ordinary 35-mm camera and aims it pointedly at precisely those places and spaces – and this applies equally to his work in the forest and in the urban environment – that would normally attract little attention, often being regarded as insignificant. In Fengel’s pictures we do not find panoramas or other compositions that would convey a classical or sublime grandeur of nature, but always only supposedly petty details that subvert every cliché of “natural beauty” in an astounding manner. Fengel illuminates the trunks, stems and leaves with a flash, so that they stand out before a deep black background, showing the unbelievable beauty of their details to the best advantage. The formal perfection and symmetry of the plants recollects Karl Blossfeldt’s Art Forms in Nature, but unlike Blossfeldt’s structural studies, Fengel’s photographs simply show the forest in its purely superficial appearance – quite apart from the fact that Fengel is not interested in constructing or deconstructing any particular reified image of nature. The temperature of his pictures is cool and their light is technical, so atmosphere is not generated. But precisely this neutrality conjures up an extraordinary, almost spiritual permeability for the magnificent sublimity of nature; one could even say a kind of humility with which Fengel succeeds in capturing its essence without revealing its secret.

Martin Fengel’s photographs defy any definition in conventional aesthetic or art historical categories. His fragmentary pictures and motifs are in themselves too abstract and indefinable to be designated as still lifes, nature photography or portraits. Rather, one could speak of gazes – gazes into a world that has itself withdrawn from all definiteness, where things no longer reliably identify with the context they happen to be in. Although Fengel takes his photos in places all over the globe, they are not culturally classifiable, and although we always recognize what is shown, we are often unable to formulate what it actually is. Fengel’s position as a photographer is similarly indefinable. His gaze is documentary, without ever reporting anything specific; and it is also artistic, but without the need to create form. Fengel worked for many years as a photojournalist, and even today we find his photographs in disparate media. He takes photographs; that much can be said. But we cannot put any label on his photography. In this aesthetic evasiveness Martin Fengel’s photography is significant for a world where the traditional notions of visual production have long since ceased to count. It expresses an attitude that is based on an awareness of the relativity of social and aesthetic convention, but also reacts with an almost programmatic openness and tolerance to the dynamics of our time. In its committed liberalness, Fengel’s photography is a social as well as an aesthetic statement, propagating the idea of impartial appreciation and finding beauty even in places where it was thought to have been lost long ago.

0304 | 2004 | INFO

0304 | 2004 | INFOSimplicity of Seeing

The Rhetoric of Beauty in the Photography of Martin Fengel

Susanne Gaensheimer

“If images don’t do anything in this culture,” began American art critic Dave Hickey’s spontaneous remarks on the idea of beauty in contemporary art (contributed on the spur of the moment in an early-1990s symposium on the state of art and art criticism), “if they haven’t done anything, then why are we sitting here in the twilight of the twentieth century talking about them? And if they only do things after we have talked about them, then they aren’t doing them, we are. Therefore, the efficacy of images must be the cause of criticism, and not its consequence – the subject of criticism and not its object. And this,” he concluded, “is why I direct your attention to the language of visual affect – to the rhetoric of how things look – to the iconography of desire – in a word, to beauty!”

Hickey’s plea for beauty, initially interjected rather provocatively and spontaneously at a conference, led in the end to a small volume of four essays on the political power of beauty in art that had some significance in artistic discourse of the 1990s. Using the example of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, whose censorship had attracted great public attention at the time, Hickey decodes beauty as one of art’s primary visual strategies that artists right back to the Renaissance have deliberately and successfully deployed to give the political and ideological content of their paintings the seductive form required for the power and ambition of the particular patrons to flow subtly and subversively into the system’s inherent network of signs and codes. Hickey’s revision of the concept of beauty in the early 1990s came at a time when in contemporary art even the slightest hint of the aesthetic still drew the stigma of the affirmative and commercialism. Now, only ten years later, Western art and culture production is characterized by an advanced disintegration of cultural categories. Reacting to the extreme social and technological developments of the late twentieth century, in the course of the 1990s art deliberately crossed the boundaries to design and commercial production, and fundamentally transformed our assessment of aesthetic values. A crossover encompassing all fields of visual and cultural production, coupled with the fundamental loss of the notion of the authentic through the virtualization of our visual experience, has dissolved the taboo between high and low and ultimately re-evaluated the alleged profanity of beauty. But all the same, we still feel strangely caught out when our first reaction to a work of art is to think: “How unbelievably beautiful!”Beauty permeates Martin Fengel’s photographs. Without really being able to pin down where it exactly lies, and knowing that in an age where we can no longer call on the classical concepts of the beautiful to talk of beauty is like walking on thin ice, it still seems to me to represent one essential feature of his pictures. Their beauty is unmistakably before me, bar any stylization or exaggeration: simple, almost subdued, and as a matter of course. Unlike other visually seductive works by artists of his generation, Fengel’s aesthetic is not refracted by the metalevel of a theory of perception, by technical manipulation or by references to the artificiality of our modern ways of seeing. Quite the contrary, Fengel photographs what he sees, simply as it appears, be this the urban civilization around him or the world of nature. That beauty is tied to the mere appearance of things – to the “rhetoric of how things look,” as Hickey puts it – is symptomatic of a time when perception is drawn more and more to surface phenomena. Channelled by the identification mechanisms of late capitalist society, increasingly defined through the superficial appearances of things, and by cognitive factors such as the radical acceleration of seeing and the interface structures of the digital media, our relationship to the world has become ever more aligned to the principle of surface in recent decades. Fengel’s photography is “superficial” in the cognitive sense of the word, because it grasps the nature of a thing through its mere appearance. This is most apparent in his photos of inflatables such as air-beds and plastic animals, which he shows in such close detail that the object itself disappears completely behind its surface. The shiny materiality and trendy colourfulness of the bulging blow-ups, their strong tension and the reflections of light on their strange, almost obscene folds break loose from the objects’ actual function and become autonomous formations with an independent, extremely decorative quality.

Martin Fengel’s understanding of beauty is deeply democratic. It is found in the normality and averageness of the everyday just as in the incredible perfection of nature. Faces of famous and unknown people fit as equals into a series of ordinary and extraordinary things and situations. What they all share, however, is the great secret concealed behind the obvious. The objects and situations that Fengel photographs in series like 0304, T and M always look like themselves, but at the same time they also look like something completely different. We all know the plastic buckets on the floor and the peculiar piece of furniture, we have often seen the garden hedge, cut painstakingly but slightly squint, and the eccentric amusement park figures where we recognize the stereotypical physiognomy of particular characters; we remember signs, materials and structures. Yet, nonetheless, the motifs in Fengel’s photographs seem so divorced from their actual context that they defy any definition. They are familiar and strange in one, specific and ambivalent at the same time. In a similar way to the photographs of William Eggleston, Fengel’s pictures formulate a poetry of the mundane, seeming both banal and highly charged; they imply – as single pictures and as series – processes and stories that run in our imagination like a film or modern fairy tale. The compositions within the photographs and their arrangement in series seem to be incidental, but both are in fact closely calculated by Fengel, in order to communicate as precisely as possible what he sees in the respective situations as well as in the relationship of these images to one another. Often Fengel takes the camera angle and perspective right down to the photographed objects, putting himself on a level with them out of a deep and sincere appreciation for their mere existence.

Fengel’s staggeringly beautiful photographs of trees, leaves, branches, and flowers in woodland or open landscape, in particular, pose the question of how the artist succeeds in reproducing “nature” without critical distance, and yet without banalizing it. In his Aesthetic Theory Adorno points out the fundamental break in Modernism in representations of nature. The idealist relationship between nature and art that determined the depiction of “natural beauty” from its beginnings in the first perspectival representations of landscape in the painting of the Renaissance, through the symbolically charged landscape painting of the seventeenth century to the last stand of the spiritual dimension in Romanticism, cannot survive man’s alienation from his environment in the modern age. Even in Impressionism, the striking intervention of technology and urbanization flows into the representation of landscape, both cognitively and in the choice of motifs, showing “wounds of nature” that according to Adorno have to be integrated in the modern consciousness. The idea of nature has been increasingly co-opted and objectified through technologization and commercialization in a development whose vanishing point Adorno sees in modern art’s recognition that “nature as a thing of beauty” can no longer be depicted: “For natural beauty as manifestation is its own image. To depict it has something tautological that, in objectifying the manifestation, gets rid of it at the same time.” In an age of the total mediatization and marketing of nature, its representation turns into “an ugly grin”.Martin Fengel’s series “Forest” does not show nature broken. It neither points to its “wounds”, which today are greater and more permanent than ever before, nor does it convey a visual experience based on the virtualization of nature in a mediatized and digitalized world. No, it shows very direct photographs of very simple motifs in the forest: tree trunks and the specific texture of their bark, a group of twigs and leaves, branches, undergrowth and the withered leafage of the forest floor. It is characteristic of Martin Fengel’s photographs that he makes no attempt at all to manipulate or idealize his motifs. Quite on the contrary, he uses an ordinary 35-mm camera and aims it pointedly at precisely those places and spaces – and this applies equally to his work in the forest and in the urban environment – that would normally attract little attention, often being regarded as insignificant. In Fengel’s pictures we do not find panoramas or other compositions that would convey a classical or sublime grandeur of nature, but always only supposedly petty details that subvert every cliché of “natural beauty” in an astounding manner. Fengel illuminates the trunks, stems and leaves with a flash, so that they stand out before a deep black background, showing the unbelievable beauty of their details to the best advantage. The formal perfection and symmetry of the plants recollects Karl Blossfeldt’s Art Forms in Nature, but unlike Blossfeldt’s structural studies, Fengel’s photographs simply show the forest in its purely superficial appearance – quite apart from the fact that Fengel is not interested in constructing or deconstructing any particular reified image of nature. The temperature of his pictures is cool and their light is technical, so atmosphere is not generated. But precisely this neutrality conjures up an extraordinary, almost spiritual permeability for the magnificent sublimity of nature; one could even say a kind of humility with which Fengel succeeds in capturing its essence without revealing its secret.

Martin Fengel’s photographs defy any definition in conventional aesthetic or art historical categories. His fragmentary pictures and motifs are in themselves too abstract and indefinable to be designated as still lifes, nature photography or portraits. Rather, one could speak of gazes – gazes into a world that has itself withdrawn from all definiteness, where things no longer reliably identify with the context they happen to be in. Although Fengel takes his photos in places all over the globe, they are not culturally classifiable, and although we always recognize what is shown, we are often unable to formulate what it actually is. Fengel’s position as a photographer is similarly indefinable. His gaze is documentary, without ever reporting anything specific; and it is also artistic, but without the need to create form. Fengel worked for many years as a photojournalist, and even today we find his photographs in disparate media. He takes photographs; that much can be said. But we cannot put any label on his photography. In this aesthetic evasiveness Martin Fengel’s photography is significant for a world where the traditional notions of visual production have long since ceased to count. It expresses an attitude that is based on an awareness of the relativity of social and aesthetic convention, but also reacts with an almost programmatic openness and tolerance to the dynamics of our time. In its committed liberalness, Fengel’s photography is a social as well as an aesthetic statement, propagating the idea of impartial appreciation and finding beauty even in places where it was thought to have been lost long ago.

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004 installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004

installation view "Sprüth Magers Projekte", Munich 2004